Editing Is a Mirror for Your Thinking—that is, the way you refine a document tells you a lot about how your mind organizes ideas, prioritizes clarity, and resolves complexity. In today’s fast-evolving environment—where AI-generated text, collaborative tools, and reflective writing apps are reshaping how we write—edit practice has become not just a step in publishing, but a window into our cognitive habits.

By intentionally observing patterns in your editing process, you can unlock insights about your internal logic, clarity of thought, decision-making biases, and clarity thresholds. In this article we’ll explore the psychology behind why editing reflects how you think, highlight the rising trend of using tools to map those patterns, and offer a practical guide to using editing as a feedback loop on your thought process.

The Cognitive Science Behind Editing as Thought Reflection

Contrary to popular practice, editing isn’t just grammar checking—it is thinking made visible. The cognitive process of editing involves evaluating structure, clarity, coherence, and rhetorical flow—each revealing underlying patterns in reasoning.

- Linda Flower and John R. Hayes’ Cognitive Process Theory of Writing frames writing as iterative, recursive, and expressive of emerging meaning: ideas evolve during revision. Editing uncovers thought development, not just surface polish.

- Writing tasks activate brain regions tied to planning, language production, reflection, and memory: working through edits requires deliberate cognitive control and meta-awareness.

This means that when you edit, you’re not correcting text—you’re examining your thinking structures. Every reordering, deletion, or clarification exposes how your brain builds meaning.

Emerging Trend: Tools That Map Editing to Thinking

As AI tools become more sophisticated, they’re not just offering corrections—they track change patterns, reflect writing strategies back to users, and integrate metacognitive insights.

- Adaptive writing support systems now log revision behaviors like frequency of restructuring or rewriting, helping users understand when and why they shift approach across drafts. Research shows these systems promote stronger self-regulated learning and revision behavior.

- Voice-based conversational AI tools let writers verbally reflect on drafts and ask follow-up questions, encouraging deeper reflection and revision. Early studies suggest that this mode helps externalize thinking and clarifies cognitive intent before editing moves begin.

- Students working with AI-generated text often focus heavily on editing, yet improvements in quality aren’t automatic—highlighting the need for reflection on content, not just surface correction. These findings underscore that editing is a mirror for your thinking and must be treated as a reflective act.

The trend shaping up now is not only about polishing text, but capturing how you think while you edit.

Why Editing Serves as a Mirror: Key Cognitive Insights

1. Reveals Conceptual Organization

When you reorder paragraphs or adjust transitions, you’re externalizing how you mentally group ideas. What flows easily? Where are gaps?

2. Surfaces Recurrent Weak Points

Frequent corrections—repetitive cuts, clarity fixes, tone adjustments—often reveal blind spots in your thinking or repetition in how you process concepts.

3. Shows Decision-making Thresholds

If you continuously pare sentences down, you may be detail-oriented and clarity-driven. If you add context and examples, your default may be expansive thinking.

4. Reflects Self-Regulation Quality

Authors with stronger self-regulated learning habits (planning, monitoring, revising) tend to engage more deeply in editing as insight development—not just cleanup. Studies show that reflective journaling paired with strategic edits supports learning and well-being.

Step‑by‑Step Guide: Use Editing to Understand Your Thinking

Below is a practical approach to treat editing as a mirror for your thinking:

Step 1: Draft Without Editing

Use Peter Elbow’s method: separate free writing from revision. Write without self-editing to capture raw thought flow

Step 2: Log Your Edits

Use track changes or editing tools that log granular changes: deletions, reorganizations, additions. Note timestamps and frequency.

Step 3: Reflect on Edit Patterns

After each draft pass, ask:

- Which parts did I change most?

- What kind of issues come up repeatedly? (e.g. vague language, unsupported claims)

- Where did I hesitate or delete entire sections?

Step 4: Create an Edit Reflection Log

Record weekly summaries like:

- Frequent edits: [Wordiness cut, concept clarification]

- Tension zones: [Transitions from idea A to idea B]

- Structural changes: [Moved sections, changed headings]

This builds a personal map of cognitive bottlenecks or strengths.

Step 5: Use Tech Tools for Pattern Insight

Try tools like adaptive writing systems or AI systems that present revision analytics—such systems help link edit behaviors to thought strategies and suggest metacognitive prompts.

Step 6: Iterate Draft + Meta-Reflection

Alternate editing passes with reflection exercises: e.g., “Why did I cut that metaphor?” or “What assumption did I clarify here?” This helps anchor awareness of how you organize ideas.

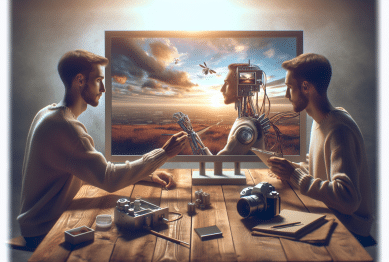

Editing for Individuals vs Collaborative Editing

In group writing, collaborative editing highlights shared thinking molds.

- Editors bring different cognitive habits; good collaboration surfaces comparison between writer assumptions and reader interpretation.

- Editors working across domains (e.g. diverse authors) sharpen strategy advice by contrasting varied thinking patterns—this indicates editing by others can magnify self-reflection.

Whether solo or team-based, editing remains a mirror.

Common Thought Patterns Exposed by Editing

Below are editing patterns you might observe—and what they suggest:

| Editing Pattern | What It Reveals About Thinking |

|---|---|

| Reordering large sections frequently | Need to refine logical flow; big-picture organization matters more |

| Cutting most sentences for brevity | Clarity and precision is a high mental priority |

| Adding examples or analogies | Thinking through concrete illustrations supports comprehension |

| Moving between passive and active voice | Awareness of tone and reader engagement |

| Rewriting repeatedly | Writer seeks clarity but might lack structured plan early on |

By reviewing logs and reflection notes over time, you’ll begin seeing cognitive themes in your process.

Why This Trend Matters: Editing Beyond Text

As AI systems increasingly generate early drafts, the value shifts from writing to thought editing—the skill of discerning and refining thinking behind the language.

- If editing is a mirror for your thinking, then training in edit‑reflect cycles becomes a cognitive fitness practice rather than a linguistic exercise.

- Education research supports this: writing—and especially reflective, self-regulated writing—is a key learning activity that enhances meaning-making and self-reflection when guided by strategies and goals .

- Recent meta-analyses confirm that structured editing and revision behavior aligns with deeper self-regulated learning and reflection—not just superficial polish.

Conclusion

When editing is a mirror for your thinking, every refinement becomes a clue. You can see your mental shortcuts, your clarity thresholds, your organization style—and use that knowledge to write better, but more importantly, to think better.

Whether you’re writing a blog, preparing professional documents, or tackling creative work, treating editing as a reflective mirror gives you insight not just into your prose—but into your mind’s structure.

So next time you revise, pause: what is this edit showing you about your thinking?

References

- Flower, L., & Hayes, J. R. (Year). Cognitive Process Theory of Writing. (Referenced in discussions of writing as thinking) https://www.wordrake.com/blog/why-knowledge-workers-must-maintain-their-writing-skills?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- Klein, P. D., & Boscolo, P. (2016). Trends in research on writing as a learning activity. Journal of Writing Research. https://www.jowr.org/jowr/article/download/658/621/553?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- Mouchel, L. et al. (2023). Understanding Revision Behavior in Adaptive Writing Support Systems for Education. ArXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2306.10304?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Why Creative Work Needs More Empty Time

Why Creative Work Needs More Empty Time